In late January the Guardian UK and other media outlets announced the news that a previously unseen movie by Orson Welles – The Other Side Of The Wind – could finally see the light of a projector. As die-hard Welles fans know, there are several lost/unseen projects out there in various states of completion including his version of Don Quixote, The Deep and others.

This isn’t the first time (and may not be the last) that someone announces the imminent release of The Other Side Of The Wind. It seems like every five years or so the movie resurfaces, like a cagey old trout that rises to the bait but won’t be caught.

The aura of mystery surrounding these uncompleted projects (most of which have been screened, at least in fragmentary form, at various cinematheques and museums world-wide) is one of the ways in which the Welles legend is kept alive, and maybe that’s not a bad thing. There’s an argument to be made that keeping some things out of sight keeps them powerful, and that no unseen Welles film, no matter how good, could live up to the one we see in our minds. (Witness the general disappointment a few years ago at director Jess Franco’s bastardized reconstruction of Don Quixote.)

Beyond their actual movies, great, charismatic directors tend to gather groups of people around them – collaborators, friends, film buffs and scholars – who also help keep the legend alive after the directors are gone. There’s still a powerful circle of Peckinpah admirers and collaborators (Peckinpahites?) here in Los Angeles who keep the torch lit.

As with so many other things, Welles may throw the longest shadow on this score. And one of the many ironies is that The Other Side Of The Wind is about the last hours of a great, charismatic filmmaker – played by John Huston, himself no slouch in that department – who’s been widely interpreted as Welles’ alter-ego.

By lucky coincidence, right around the time news surfaced of this latest Welles project, I got an e-mail from an old friend, Eric Sherman, who asked if I’d be interested in talking with him about the two weeks he worked on … The Other Side Of The Wind. As things happen our conversation wound up covering Bonnie & Clyde, big cigars, George Bush … and yes, Welles.

I met Eric years ago through the American Cinematheque where he helped organize retrospectives on directors Roberto Rossellini, Sam Fuller and others. One of the most fascinating, erudite and colorful guys I’ve met in Los Angeles, Eric has written several seminal books on filmmaking and the film industry including The Director’s Event and Directing The Film; he currently teaches production, film business and directing at Art Center College of Design in Pasadena and California Institute of the Arts (Cal Arts). You can read much more about him at his own website here. Himself an acclaimed filmmaker and producer of the Peabody Award-winning PBS Series "Futures With Jaime Escalante," Eric grew up on the inside of the film industry. His father Vincent Sherman was a highly successful studio director in the 1940’s and 1950’s who made such beautifully crafted films as Mr. Skeffington with Bette Davis and Claude Rains and The Damned Don’t Cry with Joan Crawford.

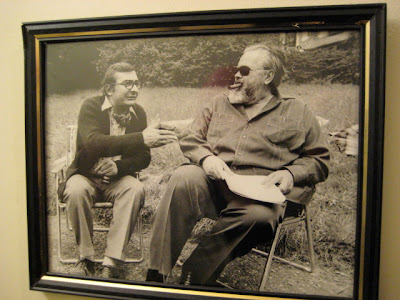

He led me inside through the garage, which now serves double-duty as his office – a convenient arrangement since Eric, a life-long cigar smoker, refuses to smoke inside the house, so instead he lights up downstairs with the garage door open. He proudly showed off a collection of DVDs of his father Vincent’s films: “We’ve got over 15 of his movies released on DVD so far,” he said with a son’s true love. An original Frank Stella hangs in the corner, near a cartoon from Sam & Christa Fuller … nearby is a photo of Roberto Rossellini with two of his “pupils,” Vittorio de Sica and Federico Fellini …

It’s a house filled with totems of art and film. In many ways Eric is an unrepentant hippie idealist who still believes in the power of art to transform us all.

|

| A son's proud collection: his Dad's movies |

One photo that stuck out in this pantheon of great filmmakers and artists was a shot of Eric with his college classmate, George W. Bush. He smiled, pointing at it:

“I went to college with Bush, he was a fellow Yalie with me and Lloyd Kaufman of Troma. Bush used to come to our Yale Film Society screenings with a case of beer and a big busty blonde on each arm. I met him a few years ago at the White House … You know me, I’m a real leftie from a Jewish background. I was totally charmed by the guy. Very intelligent. I don’t know if he’s gotten bad press or what, but in person he’s incredibly friendly.”

As he made a pot of strong black coffee, Eric kept talking:

“I’m at the age where I ask myself what we’re really doing here. As Jack Warner said, we’re here for the 3 E’s: to Educate, to Entertain, to Enlighten.

The greatest art is genre art. Shakespeare was genre. Bach was genre. A movie is a universe because it contains space, time, energy and matter – which are the components of this universe. Every movie presents an alternative universe to this one … I don’t think this universe likes film because it’s too threatening. So the artist really has to be a tough guy. Real big balls.

When my dad’s autobiography came out, Studio Affairs, we had a book signing at Sam French. Sam Fuller hobbled in – Sam had had the stroke – he and my dad embraced, they were both studio survivors. One of my students came over and thanked Sam, said he’d been a great inspiration. Sam responded with great effort, ‘what … do you want to do?’ My student responded he wanted to make films. ‘Then you gotta have … big balls,’ Sam said with great difficulty.

In 1967 – when you were 2 years old – Bonnie & Clyde was released. It was absolutely panned by critics. We saw it opening weekend and thought it was a major event. We were in the middle of the Vietnam War. We found Arthur Penn on his farm in Massachusetts. Arthur Penn was a very sweet man, very intelligent. We were 20 years old. He was quite sad about the reaction to the film. We asked him what he thought, he said ‘I’m disappointed in the reception to the film, I was trying to provide a wake-up call to the American public that if you live by the sword, you die by it. Don’t think you’re going to live by the sword and make the world safe for no swords.’ Most filmmakers I know base their failure or success on box office, even though they’re artists.

We did an extensive interview with Penn and published it in the Yale New Journal, a monthly magazine. Joe Morgenstern of the Wall St. Journal, then-critic for Newsweek who was also a Yalie – he got a copy of the interview we did with Penn and re-reviewed the film for the first time. He said thanks to an interview done with Penn by two Yalies, I realized I’d completely missed the boat on the message of the film. On the strength of that review, Warners re-released the film with a different ad campaign. And Arthur had already sold his points to Warren Beatty because he thought the film wouldn’t make anything. And he never gave Arthur even a tip. (That’s why Lucas is loved on Star Wars. I know a number of people who get generous checks from Lucas.)

In 1967 because my dad was in the industry, I was able to get these guys’ phone numbers. We went over to Sam Fuller’s house, his wife at the time had just divorced him. He was moving all his stuff out, he had this big Cadillac. He said ‘Guys, c’mon and give me a hand!’ We arrived at 2 PM and helped move him out until midnight. Then he said, ‘What can I do for you?’ We said we wanted to interview him, he said ‘Okay but let’s eat first.’ He threw 3 big steaks on the grill – one for me, one for Marty [Rubin, Eric’s partner at the Yale Film Society] and one for him – it’s some of the last meat I’ve eaten, I’ve been a vegetarian for decades. He said what’ll you drink? I’ve never been a drinker – Marty said I’ll have whiskey, Sam said ‘No you don’t, you’ll have vodka’ and poured us 3 huge vodkas. ‘Have a rope? Your dad smokes doesn’t he?’ Sam pulls this cigar out – this big, like a kosher salami – and he pulls out a railroad spike from his belt, like a guy would carry a knife, and poked the end of the cigar. He shoved it in my mouth, I was green. By 2 AM, Marty had had 3 or 4 glass fulls of vodka. Sam finally says ‘whaddaya wanna talk about??’ And we talked for 18 hours straight, and that was the interview that went in the book. We became friends and were friends for his whole life. In fact Christa gave us Samantha’s baby clothes – so my boys grew up wearing Samantha’s clothes.”

Eric took a pause. “We came here to talk about Orson Welles, right?” He jumped up and fished around for a video – a few moments later he showed me a clip of Welles on “The Dick Cavett Show.”

Eric shook his head, smiling as he remembered. “Welles was a giant, nearly 6 foot 4, in black silk pajamas … Peter Bogdanovich, who I’d met 3 years earlier when I was interviewing him for my book, called me. He said, Eric – do you still have your 16 mm. camera? Yes. You still have your friend Felipe Herba? I said, yes. Well come right over, and Peter gave us an address in Trousdale Estates, which was kind of a nouveau development in Beverly Hills which was already nouveau enough.

Orson had rented and taken over this house as a location for the film he’d started in 1970 and was still working on in 1985 at the time of his death, it’s called The Other Side Of The Wind. It’s about a cult movie director who’s having trouble finishing his last film. The movie director was played by John Huston. The picture is essentially finished – Gary Graver, the DP who was a buddy of mine, used to show scenes from it from time to time at the Fairfax. Talk about an eye popper.

So we arrive at Orson’s house and God himself steps out. We used to say 'There but for the grace of God goes God.' He was gigantic. You can see his size, he just towered over everybody. Not just physically, you could sense when he was near. Mentally and spiritually, he was huge, huge. I had become an avid cigar smoker since I was around my dad and Sam – according to afficianados, Orson was the second most famous cigar smoker after Winston Churchill.

I had bought for Orson the largest commercially available cigars at the time, a couple Double Coronas, 7 and ¾ inches long. I presented them to him, ‘Mr. Welles – from one cigar smoker to another.’ With great kindness he said, ‘Oh no thank you, Eric, I only smoke large cigars.’ He reaches in his pocket an pulls out an enormous honker ... I said where on earth did you get that? He said they make them for me. There was no commercially available size that would be more than a cigarette for him.

Let me describe the environment at this house. There was Welles, this giant figure in black, in black silk pajamas and a black robe, which is the only clothing I saw him in for 2 weeks. Various beautiful men and women were walking and running around the house, 24/7, and some of them were completely naked. It was another universe, Dennis – I was 23 at the time.

I learned that one of the beautiful women was Oja Kodar, his consort for the last 10 or 15 years of his life, with whom I’m still in touch. And it was not as though I’d died and gone to heaven, but it was as if I’d been transported to a different universe. These people were not marching to the same drummer as most.

This is how Orson would direct – he’d never look through the camera. He’d say give me a 16 right here, holding his fingers out in a circle. If I set it up here or there, he’d say ‘No!, that’s not what I said.’ He never looked at the camera but he knew if I was an inch off. And he never paid too much attention to it – except he KNEW. The certainty, the absolute knowledge that he had, was pervasive. I’m talking about a level of human intellect and awareness way above the norm. I call it learning by permeation rather than study.

I worked on The Other Side Of The Wind for 2 weeks. I was one of 2 cameras – and I acted playing a camera crew with Felipe, portraying what we were doing, which was kind of experimental for those days, a multi-camera shoot.

The general description is, we pre-lit the entire house, every room in the house. And Orson said, ‘all right, Gary – when I say roll, you roll from here, give me a 17 here,’ – holding his finger in a circle – ‘and after a minute, Eric, you start from here, and give me a 15’ – and he hold up his fingers again. A roll of film is 10 minutes long – so when Gary would roll out I’d have one minute left. Gary would race to camera position three which had been pre-planned, replace his magazine of film. He would start – and I would have one minute left and do the same.

So we’d leap frog through the house for an hour. The actors HATED this – they’d have to remember an hour of dialogue. So we’d set up over an hour of shooting – it was the party scene which was still in the movie.

Now, two sub-stories within it:

You know the famous pregnant pause in acting? Dennis, this is the pause … ‘To be or not to be, that is the question ….’ Pause … ‘whether tis nobler in the mind …’ Pause, look in the other direction.

Every place Orson looked on a pause was a cue card man. You know the famous story of Brando in Last Tango In Paris where he’s weeping over the coffin of his wife? There were cue cards in the coffin.

There were about a dozen cue card guys for Orson. One was on a ladder, another was on the ground. It was clear to me that Orson never read the cards though he looked in their direction. It was the ultimate security blanket. The cue card company was called Barney Cue Cards, and Barney just passed away a few years ago, wonderful guy.

The second story was this… You understand I have an obligation to have my lens exactly where Orson said, right? My camera position three was very awkward, I’d be crouched like this bent over, too high to sit. On about my 3rd or 4th camera position – 30 or 40 minutes into this – even though I was 23 and in good shape, my back starts really cramping, I grab my back and stand up. Orson says CUT! Eric, how do you expect me to concentrate with all that motion???! Now Dennis, there are a dozen guys running around, guys with cue cards, guys on ladders – I make one motion and he says cut!

I say Mr. Welles, there’s 30 guys running around all over the place.

He says ‘Yes – but I didn’t plan yours.’ He could tolerate infinite motion – if he put it there. But one motion of 12 inches he couldn’t tolerate.

I said that’s genius. Now I know what a genius is. That’s the way the shoot went.

The crew turnover was 50% a day, because not everybody could take that degree of intensity. I lasted two weeks.

Our call time every morning was 6 am. Wrap time was 2 am. Meaning we had a 20 hour work day, which was quite illegal. But nobody complained, they just quit. When we wrapped at 2 am, Orson would be sitting at his typewriter typing the pages for tomorrow. We’d go home, take a shower, lay the body home for an hour. We’d come back at 6 am – and he’d still be sitting at the typewriter. Meaning I didn’t see him sleep for 2 weeks. You get that image? In the same goddam black silk pajamas and robe.

We had one meal break every day, it was a 2-1/2 hour lunch. Catered by the Beverly Hills Hotel or Chasen’s. When it was Chasen’s they’d bring buckets of their famous chili. I never saw Orson eat.

While we would be eating he’d be recording Eastern Airlines and Gallo Wine commercials. Am I describing to you an eccentric man? Gigantic in size, I never saw him eat, I never saw him sleep.

There’s a famous scene in the movie. The female lead is played by Oja Koda. She has sex with the driver of the car – I think played by Bob Random, in the Boetticher film A Time For Dying, and they really go at it, it’s one of the more erotic scenes ever. We were driving through Century City at 5 am one morning. Remarkable point: Orson – this is the days before video monitors – Orson wanted to be present in the car. Not because he feared anything sexual – but he directed by permeating a setting, and he just infused in us all the knowledge of what he wanted.

Now a man Orson’s size couldn’t fit into the car really. It was a Lincoln Continent Town Car, which had the largest trunk of any car made at the time. I hope this doesn’t sound insulting because I really love the man – he insisted we lower him into the trunk, and cut a little hole in the trunk through the back seat so he could see. It took us about 2 hours to lower him into the trunk. But given his size and height and weight, it took over 2 hours to get him in. And then we closed him in. I was afraid he’d suffocate but he didn’t. So we drove around Century City while Oja and Bob Random were simulating fucking in the front seat.

So the 2 weeks go by and we wrap that sequence of scenes. And this led to the Event that inspired me to contact you and say I’ve got an L.A. After Midnight story. All of this was a preamble:

It was around midnight and we wrapped. Orson said, ‘Eric, you seem to know the town pretty well – what’s open late? I want to take everybody to a wrap party.’

There was a Mexican restaurant – still is, I think, in the Silverlake area called Nayarit, near Barragan’s, on Sunset near Alvarado. So 15 or 20 of us drive over there and we start dinner about 2 am. And the place is normally open till 4 am but they stayed open for us until 6. And that’s when I saw Orson consume more food and drink than I’ve ever seen anybody eat. He ate continuously for four hours. Every form of Mexican food, just platter after platter. And pitcher after pitcher of margaritas. During that four hours, I sat next to Orson – we talked about everything I wanted to talk to him about. Art and film and women and politics.

I’d like to tell you three things he told me that night that always stayed with me:

Number one, his favorite artist was Duke Ellington. Duke was to music as Orson was to film. He spoke so lovingly of Duke.

The second thing he told me was that he hated Richard Nixon for one reason. My generation used to burn the American flag as a protest. Nixon made that illegal and would pursue anyone who’d burn the flag. Orson said, ‘how stupid could you be? A flag is a symbol. How could burning a symbol be a crime?’

The third thing was, I would say Orson probably had had his share of women, beautiful ones, being married to Rita Hayworth and consorting with Oja. And he stated to me his view of women. He said obviously, women are the superior gender. Obviously. They go through child birth – we men appear to be stronger but that’s because we puff out our chest. Why are we doing it? To impress women. Physically, mentally and spiritually women are superior.

We embraced, we wrapped – and Orson continued to shoot the film for 15 more years.

I’m going to give you a coda. Approximately 14 or 15 years later, Doug Edwards [former head film programmer at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences] called me. A very good friend, a true gentleman in every sense of the word.

He called me and said, Eric, would you like to produce a film to be written and directed by Orson Welles? I said Doug, was Christ Jewish? Give me a break, what’s the script? He brought me a copy of a script Orson wrote called “The Dreamers.” It was a combination of three short stories written by Isak Dinesen, the character played by Meryl Streep in Out Of Africa, a Danish woman whose real name was Karen Blixen. She’s the only person Orson spoke of, of whom he was in absolute awe. He’d fly to Denmark and stand in front of Dinesen’s flat, awe struck.

So “The Dreamers” is probably the greatest screenplay that I’ve ever read … Mindboggling, huge, about an opera singer named Pellegrina in Europe. It’s about the nature of creation. All I can say is it’s an older artist’s testament like Bach’s the Art of Fugure or Beethovens 9th, or Brakhage’s final works. Stunning.

He had prepared a budget, at the time it was about $10 or $12 million. I said to Doug, I’d love to talk to Orson about this. So I had one more meeting with Orson, just before he died, in 1984 or 1985.

I said to him, ‘Doug has asked me to produce this, and I have a question for you. If I produce it, I’m going to be responsible to the investors to watch their money. And you have a reputation for being profligate with investors’ money, and I want to know, do you think I ought to take on this assignment?’

Orson looked up wistfully in the air, then he said: ‘Eric, I don’t think you should.’ I said, why?

‘Because I hate people with money,” Orson replied. ‘So if you produce it, I will abuse you – and the investors’ money. I’ll keep writing scenes rather than finish the film.’

Dennis, do you get how moving this was to me? He was stating right there the key to his life and career.

I’ve always thought that, on the one hand, I didn’t help a group of investors lose $10 million – and on the other hand, we don’t even have the shards of a lost masterpiece. So I’ve had mixed feelings about that.

But I think I grew up really during that meeting, because I no longer looked at Orson as a blighted artist. I looked at him as self destructive – with awareness. That was a profound realization.”